How We Manage Our Tech Stock Portfolio

Table of contents

If you’re managing other people’s money, don’t assume everyone measures their time horizon in decades. People often panic when they see their account balances plummet as the market undergoes some turmoil. In the investment management world, the term high-water mark describes the highest value a portfolio has achieved. The term drawdown describes the difference between the highest value your portfolio has achieved and the lowest. You can be sure when a client calls to complain about their portfolio performance, they’re comparing the high watermark to their current balance.

Someone recently asked us how our portfolio was performing. How long is a piece of string? Until we sell a position, we have not realized any profits or losses. We haven’t sold many positions since we started, but we have been doing lots of buying. When we buy a stock, we do so very slowly. That’s prompted quite a few questions from our subscribers about how we go about buying tech stocks. Today, we’ll walk you through the rules-based approach we use to manage our tech stock portfolio.

How We Buy Tech Stocks

The method we use to buy tech stocks isn’t a science, nor is it strictly rigid. What’s important is that we have a method of adding stocks that’s structured to help us avoid market timing. Let’s start by talking about target weightings.

Target Weighting

We have a simple rule to figure out target weighting for any stock in our portfolio. Divide one by the total number of stocks in our portfolio. Since we have 37 stocks right now, that comes out to 2.7% (1 / 37 = 0.027). So, an equally weighted portfolio would contain 37 stocks that each constitute 2.7% of the portfolio value. Here’s what that looks like.

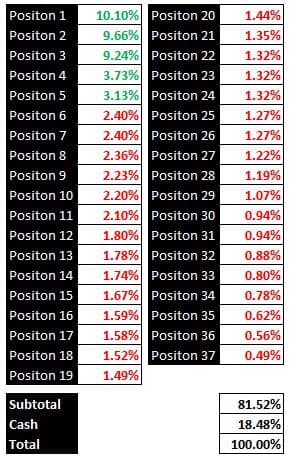

When we look at the weighting of any given position, we can quickly see if it’s overweight or underweight. We also set a cap that says we start trimming a stock if it exceeds 10% of our total portfolio. Therefore, we do not add to stocks that have a weighting of 2.7% or more. Here’s what our current weightings look like.

Green text positions are over our target weighting size of 2.70% and red text shows positions under our target weighting of 2.70%. Around 18% of our portfolio remains in cash which can be used to add to existing positions. This is a good segue into talking about how we buy a stock when we open a new position.

Target Capital Allocation

Our rule of thumb is to start a new position at one-third of our target weighting. We’ll use C3 (AI) as an example. Let’s say we opened a third of a target position size in C3 several months after their IPO debuted at $66 a share. Here’s what that weighting would look.

- C3: 0.89% weighting

Now, let’s say seven months have passed and the stock price has fallen to $45 a share. All things being equal, our weighting has now fallen to 0.64%. Before we add shares, we need to think about “target capital committed.” How much of our total capital will we commit to C3 if the stock price keeps falling over time?

Setting target position sizes by weighting doesn’t help us limit the dollar amount of money we allocate to any given position. Here’s how we calculate the maximum amount of money we’ll invest in any given stock.

- Multiply <Target Weighting> times <Total Portfolio Value>

Let’s say our portfolio is valued at $100,000. The target capital for any position size – the maximum amount of money we’ll invest in any given position – is $2,700. Regardless of what our current weighting is for any given stock, we won’t add to a position if we already contributed our target capital allocation. It doesn’t matter how low that stock price drops. This keeps us from trying to catch falling knives.

So, let’s say we established a position in a stock with a third of our target capital allocation. After a few months, the stock price has fallen -20% (tech stock prices are volatile, so this isn’t out of the norm). How do we decide when to add to our position? The first thing we consider is something called “cost basis.”

The Concept of Cost Basis

Cost basis is simply the average price-per-share you paid for your position. Here’s an example showing the cost basis for a position that’s been purchased across multiple price points.

In the above example, the cost basis is $948 or $11.15 per share. If the price of shares trades at $5.58, that means shares are trading at -50% below our cost basis. Now that we understand the notion of cost basis, let’s look at how we use this to add to existing positions.

Adding to Existing Positions

Once we’ve established one-third of a position size, we wait. If shares go up, we’re happy. If they keep going up and eventually the company becomes the next Microsoft, we’re happy. As they say, “if it’s the next Microsoft, all I need is a little – if it’s not, I’m glad I only put in a little.” However, if the share price falls, we’re also happy, because we can now purchase a quality asset on sale.

When a position falls below our cost basis by a certain amount (right now that’s -30% to -40%), we then look to start adding shares. When we tell our subscribers we’re adding shares, we try to do so on a Monday so we can add over the entire week. Our unwritten rule here is to add a fixed amount of money every day for each trading day. That amount is usually the same over time and amounts to about 3-5% of our target capital for that position, per day. So, over the week with five purchases we would be committing an additional 15% to 25% of our targeted capital amount. Once we commit all the capital, we’re done. Going back to our earlier example of a $100,000 portfolio with 37 tech stocks, here’s what that would look like:

Our initial rule was to say that if a position fell -20% or more below our cost basis, we would start adding shares slowly. Now that the market is hitting the skids harder than a Portland smack addict, we’ve changed that to -30% to -40%. That may sound like a heavy loss, but just remember how bad things can really get.

Value at Risk – VAR

Companies like MSCI produce risk management tools that let you do some pretty cool stuff. For example, you can stress test your portfolio to see how certain market events would impact it. Events such as the Gulf War, the Housing Crisis, and the Dot-Bomb debacle can all be selected from a dropdown menu and the impact to each stock displayed for you to see. One metric these tools will produce is called value at risk or VAR and it answers this question:

- Tell me – with 95% confidence – what is the maximum amount of paper losses I might incur if bad stuff happens?

We don’t need an enterprise software tool to answer that question. We can just look at history. The drawdown in tech stocks when the dot-com crash hit was somewhere around -80%, even for big chip names like Intel and Cisco. So, if you had a $100,000 tech stock portfolio, it would have a balance of $20,000. You would have then needed to wait 14 years for your portfolio to return to its original value of $100,000. If that sounds like something you wouldn’t be able to stomach, don’t invest in tech stocks. Or at least allocate a fixed percentage of your total assets to tech stocks and only invest in quality stocks.

Adding a New Position

If you’re a hiring manager recruiting for an in-demand job, you’ll receive a lot of resumes. One way to quickly vet candidates is to look for red flags. People who pay attention to detail don’t have typos on their resume. There is never any good excuse for showing up late for an interview. Don’t badmouth your old boss. And the list goes on. The same holds true when we’re vetting tech stocks.

Most stocks we come across we end up avoiding for any number of reasons. Some we may like, but we then need to consider how they fit into the context of our current portfolio. Since we come across lots of exciting stories, we put a limit on the maximum number of stocks we’ll ever hold in our tech portfolio – a target of 36 and a hard stop at 40.

Right now, we’re holding 35 stocks and two ETFs. Since we’re not going to hold ETFs going forward, that means we have – at maximum – five open slots available for new stocks which we’re in no hurry to fill. Now that our portfolio is largely constructed, we’re moving to maintenance mode. That means we may sell a stock if the thesis changes, or add to a position if we see some bargains.

Today, we’ve talked about how we go about buying tech stocks, both ones we already hold and new positions. The process of determining which stocks we want to invest in, to begin with, is covered extensively in our investment methodology which we continue to refine over time.

Conclusion

Now that we’ve made our buying process as clear as mud, you may have some questions around why we do things the way we do. We’d like to have some sophisticated methods underlying these rules but there aren’t. It’s simply a process that’s evolved over time into a methodology for how we buy tech stocks for our tech stock portfolio.

The exact method isn’t important, but what is important is for everyone to have a method to buy stocks which doesn’t involve trying to time the market. You’ll never buy at the bottom, and you’ll never sell at the top. But what you can do is try and minimize your market timing risk by putting objective rules in place to manage your tech stock portfolio.

Sign up to our newsletter to get more of our great research delivered straight to your inbox!

Nanalyze Weekly includes useful insights written by our team of underpaid MBAs, research on new disruptive technology stocks flying under the radar, and summaries of our recent research. Always 100% free.